The Carbon Tax Is Not Why Life Has Become So Expensive

Shifting incentives for a greener planet

“Show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome.”

This well-known quote from the late Charlie Munger – a legendary investor and Warren Buffet’s right-hand man – is one of my favorites. Charlie is pointing out that you can determine what people will do in any situation if you understand how they will be rewarded or penalized for different actions. As he puts it:

In my view, many of the problems we are dealing with today are a product of bad incentive systems that encourage people to behave in ways that degrade the well-being of society as a whole.

One example is housing, which Paul touched on in a recent interview with Global News:

“For decades now, too many governments have been asleep at the wheel. We’ve all tolerated home prices leaving earnings behind. We did so because homeowners like me (I’m 50), and older than me, got wealthier as the values of our homes went up.”

The majority of Canadians who own their homes are incentivized to enjoy, not protest against, rising home values. That’s because prices going up means homeowners are gaining wealth as they sleep. And with 1 in 5 Canadian homeowners owning more than one property and nearly half of our political leaders owning real estate investments, there are even fewer reasons for our elected representatives to stop prices from spiraling out of control. (Note that a Generational Fairness Task Force or Commissioner focused on ending intergenerational extraction could’ve changed the equation here!)

The carbon tax operates on the principle of incentives

In the past, there were few consequences for polluting. Nobel-prize-winning research shows that people and businesses pollute more when it’s free or cheap to do so. Putting a price on pollution via a carbon tax makes polluting more costly, encouraging all of us to adopt greener behaviors. It also makes innovative eco-friendly business models more cost-efficient, leveling the playing field by placing a cost on the environmental impact of emission-heavy firms.

Despite scientific evidence about the simplicity, efficiency, and fairness of pollution pricing as a tool to help reduce Canada’s high per-capita emissions, the carbon tax has become highly controversial. Canadians initially supported pollution pricing and opposed provinces opting out of federal climate plans. However, in recent years the carbon tax has been widely politicized by the ”Axe The Tax” campaign.

Paul’s recent article in The Globe and Mail explains why we shouldn’t fall prey to such misguided slogans.

“Whenever I hear politicians propose to cut the carbon price, I can’t help but think back to my childhood growing up with divorced parents.

On the rare occasions my dad took me for weekends, he would offer me candy and let me stay up late.

‘Why can’t you be more like him?’ I’d yell after returning home as my mom made me do my homework, eat vegetables and go to bed on time.

So it is with proponents of Axe the Tax. They offer us candy, when the federal government, like my mom, expects us to live responsibly.”

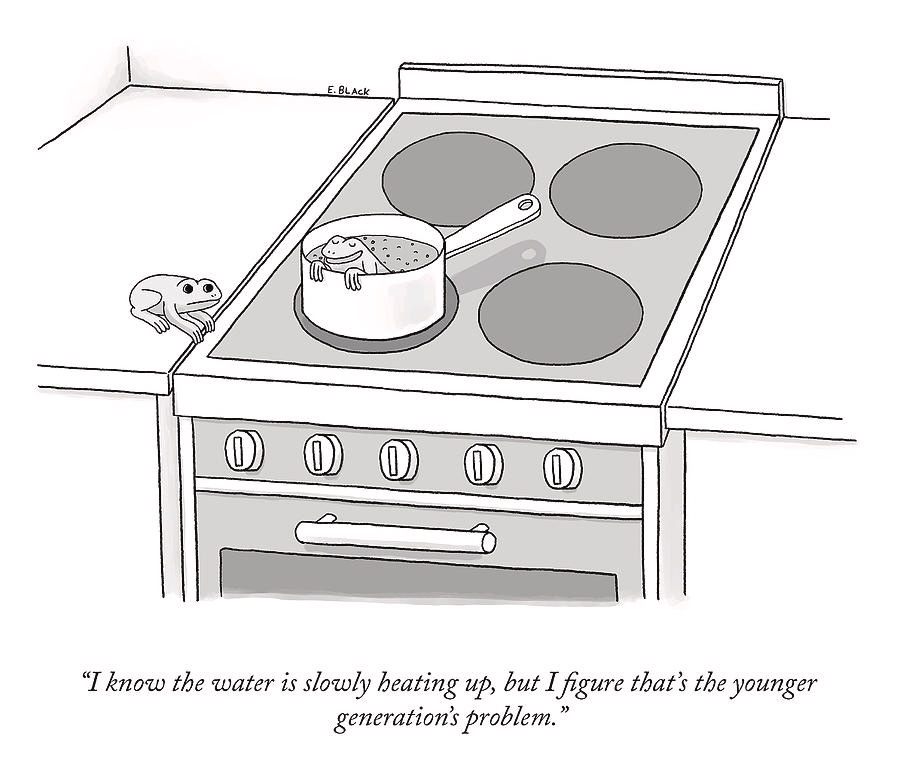

We can’t afford to avoid eating our vegetables anymore. We know from the housing crisis that kicking the can down the road only means a bigger mess to clean up later. When it comes to climate change, we are rapidly approaching “points of no return”. That means that we might never have a chance to fix the mistakes we are making now.

Paying for our pollution isn’t only the right thing to do to repair the risky legacy we’re leaving to our kids and grandkids. It also doesn't cost as much as alternatives, like regulation or subsidies. And as Paul describes in the article, the impact of carbon pricing on the finances of most households is small, despite political claims to the contrary:

“…research conducted at the University of Calgary shows the carbon price contributes less than 1 percent to our major costs of living, such as rent and food. The rebate we get back is more than what most of us pay for our pollution.”

Since the carbon tax is not the source of our financial hardships, axing it is not the solution. We have to look elsewhere for solutions on affordability.

Ultimately, someone will have to pay for our pollution. As Paul explained on Parliament Hill a few weeks ago:

Let’s be good ancestors, and stand with leaders resisting short-term thinking. As Hart Jansson, a friend of Gen Squeeze put it, “If we ‘Axe the tax’, then we ‘Shirk the Work’”, something younger and future generations of Canadians cannot afford for us to do any longer.

While we’re on the subject of unpaid bills, we also want to share our latest episode of Hard Truths with guest Sean Speer, editor-at-large for The Hub:

Taxes, deficits, and Canada's fiscal reckoning

Governments of all party stripes, across Canada, must confront a gnarly problem when it comes to investing more fairly in all ages. How do we pay for the ballooning retirement costs of baby boomers, without skimping on the needs of younger people and burdening future generations with massive public debts? And more basically, how can we have "adult con…

I think there's some gap between the ideal of not imposing costs on future generations (agree!!) and political choices about how to get there and how the costs are shared between current generations. Despite evidence the carbon tax is more efficient than other measures, it's not obvious that the government is acting like it believes it (even aside from regional pandering). Especially on housing, we've seen a big change in the kinds of development being pushed that picks winners, pre-determines the appropriate trade-offs, and restricts choice about how to adapt--all things that in other contexts are seen as a disadvantage of direct regulation. Particularly, the push for density over allowing cities to grow as populations grow assumes that it's going to be housing (and mostly housing for new buyers/renters) that adapts more than transportation does. This seems like an odd choice in a world where hybrid work seems here to stay, where electric vehicles will reduce emissions somewhat, and where the carbon tax itself is likely to shift people's choices both about where they go and how they get there.

I do appreciate that the fact that housing built now bakes in certain trade-offs for the long-term, plus land-use considerations, makes it different in at least some ways from other kinds of consumer choices. But, while I personally support the carbon tax, I can see how it becomes a hard sell when it's in practice not coming as a substitute for more onerous measures but on top of them.

"And with 1 in 5 Canadians owning more than one property"

It took 3 people to write this and none of them thought this stat was odd, it's 1 in 5 Canadian property owners, not all Canadians. Congratulations on your poor reading comprehension. There's hardly any information in this 'article' either. Don't quit your day jobs lol.