Outdated Policy Decisions Are Haunting Young Canadians

Unsustainable Old Age Security Payments and Short-Term Rental Restrictions

In this issue:

Before diving into our stories for this week, we’d like to formally invite you to our first-ever Gen Squeeze community call on November 16. We’ll be talking about how past policy chickens are coming home to roost. For several decades, governments made short-sighted policy decisions that are now eroding Canada's promise to younger and future generations. If you’re interested in discussing these generationally unfair policies, and how they’re contributing to today's housing, affordability, medical care, and climate crises, this call is the place! You can register here.

You don’t have to look far to see how public policies affect our day-to-day lives. Today we’ll discuss two examples that illustrate how significant these impacts can be. The first explains how a decades-old misguided policy is now hampering our federal finances. The second is a recent policy update with an immediate impact on BC’s housing market.

The rising cost of Old Age Security is weighing on our Federal budget

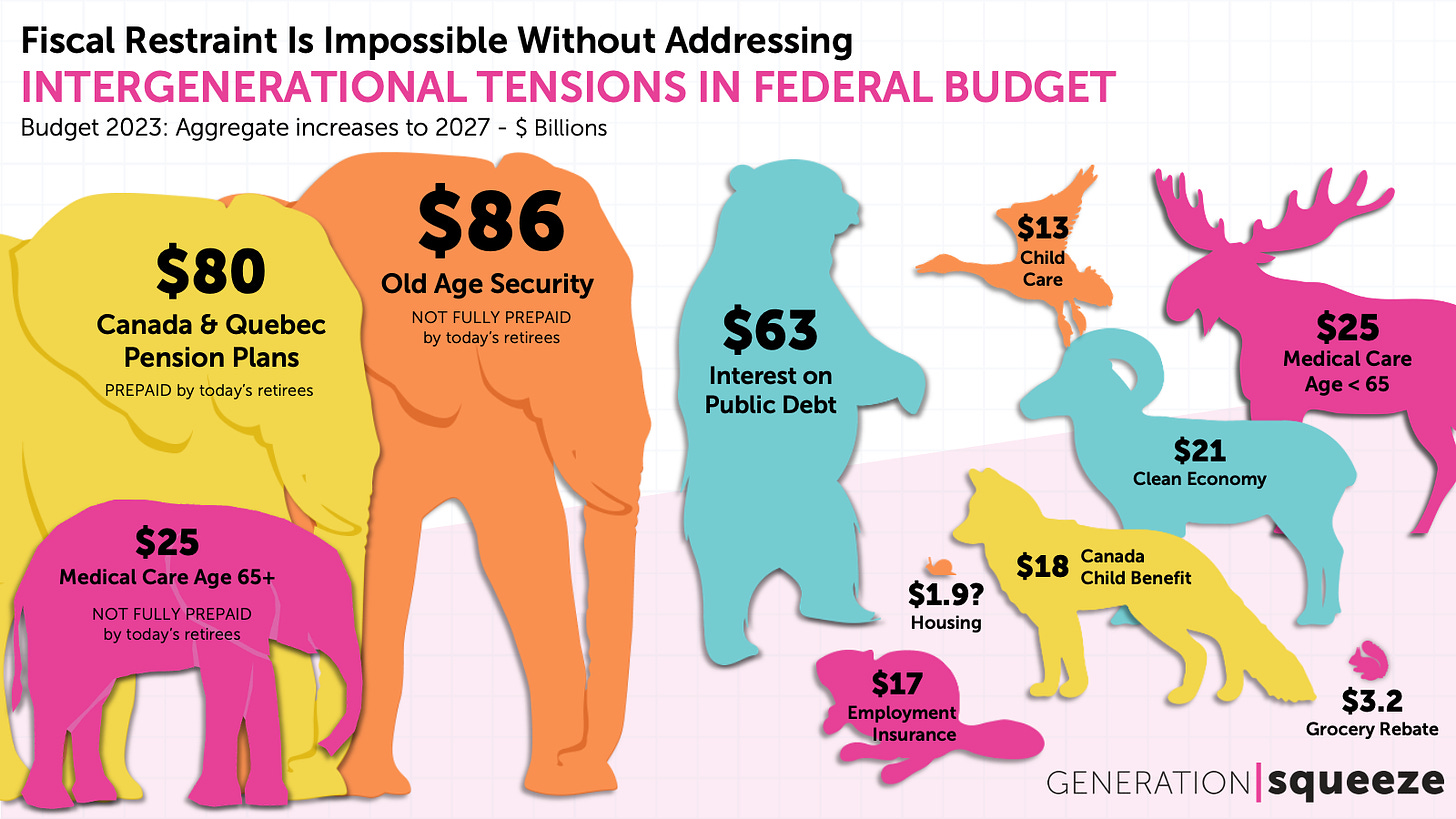

Earlier this year, the federal government released its latest budget, announcing $190 billion dollars in new spending over the next 5 years. Where would you guess the biggest portion of this new spending is going?

Investing in making housing, and life generally, more affordable?

Building a cleaner economy?

Helping families to afford child care?

Reasonable guesses, but far from reality. Old age security (OAS) is the winner.

All of this new spending means that Canada is projected to accumulate $132 billion of debt over the next five years. This debt is largely being used to offset the soaring cost of OAS payments, as well as increased spending on medical care for seniors. We’re funding new spending for our aging loved ones by adding $6100 to our national debt for every person under 45.

In Paul’s most recent Globe & Mail column (full article here), he explains how poor decisions made decades ago are weighing on our budget – and how prudent actions taken today could begin to remedy the situation. Here’s the crux of the issue:

“Decades ago, politicians chose to ignore the predictable implications of the demographic bulge represented by the baby boom. During their working years, baby boomers paid taxes when there were seven working-age adults for every retiree. Now, in retirement, boomers expect the same or better supports when there are only three working-age Canadians to pay for every senior.”

We failed to account for the fact that baby boomers would draw more out of the OAS and medical systems than they paid into them. Now, we’re funding the difference with debt that will be passed on to younger and future generations.

Gen Squeeze has identified two tax credits that we could do away with to help make important programs like OAS more fiscally sustainable. The Age Credit gives a tax break to any Canadian age 65+ with an income of up to $92K. The Pension Income Credit allows seniors to automatically shelter a portion of their pension income from taxation regardless of total income.

“... the Age and Pension Income Credits date back to 1987, when poverty rates among seniors still lingered near or above those of younger people. Together these credits drain $6.4 billion annually from the federal budget. Some, or all, of this money could be redeployed to help cover the growing cost of OAS.”

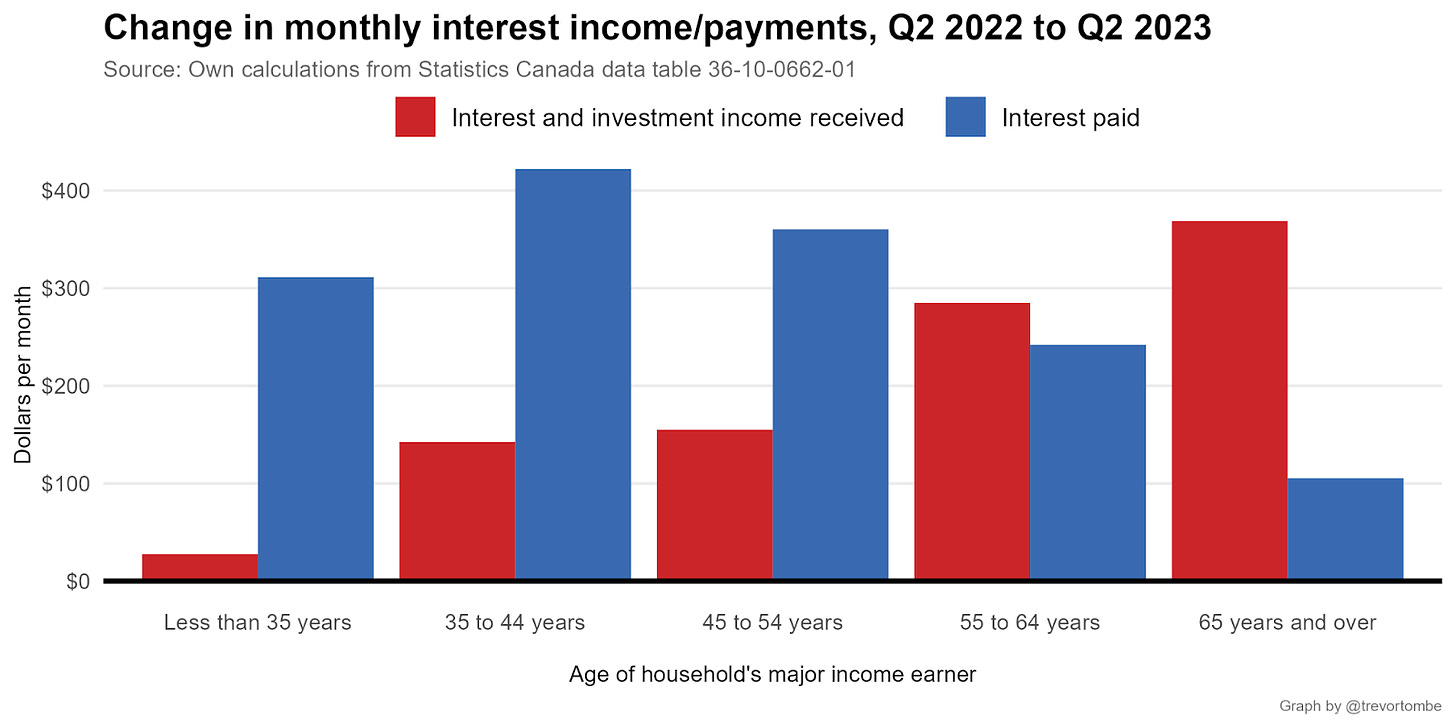

These credits were implemented at a time when older Canadians were not doing very well financially, but times have changed. For example, the data in this chart illustrate that higher interest rates have largely been a burden to younger Canadians, but a boon to older ones.

It’s time to recognize that older Canadians are no longer the demographic that is experiencing the most economic insecurity. This vulnerability has shifted to younger people, and we need to update our tax policies accordingly.

New podcast episode: Jerry DeMarco on institutionalizing generational fairness

How can we make governments consider the impact of their decisions on future generations? To find out, Gen Squeeze’s Andrea Long and Megan Wilde spoke with Jerry DeMarco, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development in Canada’s Office of the Auditor General. He’s the closest thing Canada currently has to a generational fairness watchdog, tasked with holding the federal government to account for its sustainable development promises.

“When we didn't have the technology to create multi-decade or multi-century messes for others to clean up, then there wasn't necessarily a need to have institutions that could deal with that. But now that we do have that ability to create these long-term problems, we need to harness our ingenuity to figure out new ways of addressing them.” - Jerry DeMarco

The conversation touched on:

How Canada went from leader to laggard on climate action

Comparing sustainable development and generational fairness

How Canada and other countries can embed long-term thinking in government decisions

You can find the full episode here.

BC introduces restrictions on short-term rentals

“Anyone who’s looking for an affordable place to live knows how hard it is, and short-term rentals are making it even more challenging”, said Premier David Eby. “The number of short-term rentals in B.C. has ballooned in recent years, removing thousands of long-term homes from the market. That’s why we’re taking strong action to rein in profit-driven mini-hotel operators, create new enforcement tools and return homes to the people who need them.”

Gen Squeeze has long argued that we need to treat housing more as a place to call home, and less as a way to get rich. That’s why short-term rental regulation is one tool to ‘dial down harmful demand’ in our comprehensive housing policy solutions framework.

We are thrilled to see that BC Premier David Eby and Minister of Housing Ravi Kahlon are on the same page.

BC’s new rules will focus on:

Increasing fines and strengthening tools for local governments

Returning more short-term rentals to long-term homes

Establishing provincial rules and enforcement

Gen Squeeze helped to lead the successful push for early regulation of short-term rentals in Vancouver and Toronto, to prioritize housing as homes for locals rather than accommodation for tourists. We also co-created a toolkit to help communities to regulate this sector.

We hope that BC’s actions will inspire the Federal government to implement country-wide regulations to help turn more short-term rentals into long-term homes. Housing Minister Sean Fraser suggests that more measures are coming in the upcoming Fall Economic Statement, so stay tuned.

While BC is leading the way in Canada, regulating short-term rentals is not a groundbreaking idea. Portugal, another country dealing with extremely unaffordable housing, banned new short-term rental licenses earlier this year. NYC has also been cracking down on Airbnb. They’ve proven it can be done, so cities like Ottawa and Hamilton – which have more expensive housing than NYC relative to income – should also get on board.

That’s all for this time, thanks for reading.

We’d love to hear what you think about all of this. See you in the comments section.

I agree with Valerie that expectations from boomers are outsized. Every financial planner talking to a soon to be retiree tries to maximize CPP and OAS income no matter how wealthy a boomer might be in terms of assets. It’s free government benefits (esp OAS) so you’d be a bad financial planner not to plan to take as much as you can get.

And then there’s the life expectancy issue... retirement age was based on actuarial calculations. Back in the 1970 life expectancy was 72 years old. In 2023 it is 83 yrs old.

So government pensions and OAS need to paid out at least 10 yrs longer than originally planned for. This is particularly painful when it comes to OAS since it comes from general tax revenues.

So should benefits now start at 75 years old? Would seem to make sense...

One thing that makes it super hard in my experience to convince older people that they underpaid for OAS (and healthcare) is that it's not just that governments failed to plan for baby boomers' retirements, but that they allowed that unusual demographic tailwind to set people's expectations for what safety nets should be able to do and at what price. Canada got universal healthcare federally in 1968 (oldest boomers 22). GIS was introduced in 1967 (oldest boomers 21). The age to receive OAS started to be lowered to 65 in 1965 (oldest boomers 19). Even the CPP (although it was since fixed) was brought in with an unsustainable pay-as-you-go form in 1966.

So even if you manage to convince someone they underpaid, they might respond: yeah, that's how it works! We just never really had a recognizably-modern system that even accounted for a stable population, let alone a big demographic bulge like the baby boom.